I was watching Mastermind recently and found a contestant had chosen Alan Partridge as his subject. My reaction was a combination of being thrilled to be responsible for something that was being asked about on Mastermind, while thinking: "God, Mastermind's gone downhill a bit, hasn't it?" I sometimes find myself lowering my opinion of a body when it asks me to appear in front of it.

And yet comedy matters to a lot of people. Surveys show that a high proportion of people aged 18 to 36 get most of their information about British politics from Have I Got News For You. In America, similar figures show that Jon Stewart's topical comedy The Daily Show supplies a high percentage of 18 to 36-year-old Americans with their main news fix.

Why is comedy taking up so much space in our culture? Why is it so present, so dominant? There are things that should matter more - but at the moment they just aren't there.

I had a salutary experience of this around our breakfast table. The family were talking about jobs, what the children wanted to do when they grew up; all sorts of useful professions came up, teacher, nurse, doctor, anything really. I told my seven-year-old son: "You can always write jokes." "Daddy," he said, furiously. "That's not work."

It's what I suspect most of us who work in the creative arts occasionally feel: that what we're doing is interesting, it's fun, it's probably the only thing we can imagine ourselves doing. But is it a proper job? Is there a point to what anyone in the arts is doing? It's only recently that I've come to find out that it does - that spending one's life just imagining things, making things up, performs a crucial role today. It matters because it's an act of imagination, and imagination is one of the things that defines us as human beings rather than monkeys. It's an act of imagination that is just as valid, just as crucial, I think, as any serious competitor, like a drama or the novel. But I think we sometimes see comedy as an inferior art form.

This irks me. Comedy allows the imagination to be at its most revolutionary. Because, when you treat something comically, you can do anything. You can distort or exaggerate, you can break out of the form, you can be as real or as unrealistic as you like. You can invent, you can deny, hide or reveal, be as free or as controlling as you like. The most groundbreaking novels are usually comic. In return, though, you make a devastating pact with your audience. Because, though you can pour all your energy into doing any of these things, if they're not funny (worse still, if they're not instantly funny) then you're a failure. No court of appeal.

That's why, over questions of taste and taboo in comedy, my instinct is always first to ask: is it funny? That's why I probably would have had more sympathy with the Christian protest groups if Jerry Springer: The Opera had been less amusing, and would have had more sympathy with the Danish cartoonists if their efforts in depicting Muhammad had been more witty. And I'm sure the Labour MP Sion Simon - who parodied David Cameron's web diaries with a send-up of himself dressed as a yoof called Dave, inviting people to sleep with his wife, because that was cool - would have earned less derision if his material had been not so dire. Simon defended his efforts on the basis that it was "just satire". No, Sion, it was just bad.

I thank my lucky stars I'm not elected, like a politician, and don't have to arm myself daily with opinions, arguments and reactions that hang together and stand up to examination. I don't have to have a recognisable point of view or ideology; and, if all else fails, I can always change my mind. So long as it's funny. It's the privilege of being irresponsible.

But here is the confusing bit. Despite this, I still want comedy to matter a great deal. I want it to tackle big subjects. The idea that we are making someone laugh about something does not mean we don't take it seriously. Sometimes, we can take something so seriously that the only practical way to release the tension is to make a joke. Sometimes, we can be so appalled by someone's behaviour that the only effective way to run it again in our heads is as farce. Luckily, we do not live under tyranny, but those who do so know the creative freedom the joke gives them. You can ban writing, but you can't stop people finding things funny.

Similarly, being serious is not a sufficient reason for tastelessness or taboo-busting. A piece of television I found offensive recently was a documentary about Gorecki's Third Symphony. One movement contains a setting of words scrawled by an 18-year-old girl in a Gestapo cell. This music played over scenes from Auschwitz. I found myself getting angry at this, because what was happening was that images of real death and real trauma were being used as a background visual to illustrate and promote an already commercially successful piece of classical music. Regardless of the serious intent of the composition, I did find myself wondering what it is about "high art" that gives it the right to plunder our experiences in this way. If I had set those same scenes to, say, a Frank Sinatra classic, I would have an awful lot of explaining to do. So why not here?

I should be honoured that comedy plays such an influential part in cultural life. Look at politics. So much of it today is conducted in the form of a joke - not necessarily an amusing joke - that it's practically impossible for a professional jokesmith to go one better. After Sion Simon's "satirical" send-up of Cameron on YouTube, is there really any room for a comedian's more professional parody? When Gordon Brown has to get comic writers to supply him with some gags about the Arctic Monkeys and the Arctic circle, is there anything left for a comedian to say? When the only way a Prime Minister can get round his wife publicly calling his Chancellor a liar is with a joke, then what's left for a joke-writer to do? Comedy is so prevalent now, it's cool by association. So politicians speak and act according to the rhythms of comedy. Labour trying to portray Cameron as a chameleon - it's an attempted sketch.

This has come about for three reasons: politicians have stopped speaking to us properly, the media has stopped examining their actions in anything like a forensic way, and broadcast culture has become so watered down, so scared of fact, that people are less inclined to turn to anything other than entertainment for information.

Broadcast journalism today promotes itself not so much on what it talks about but on the method it uses: "Broadcasting 24 hours a day, correspondents in over 50 capital cities, giving you all the headlines every 15 minutes, up to six generations of journalists gathered in one newsroom, making you feel all the news you want to feel, even on Christmas Day." Hi-tech software and speedy transmission makes everything instant news, but we lose sight of the skilled individuals who can process this random unstoppable flow of information and somehow construct a meaningful examination of it. We need narrative.

I found myself hungry for narrative in the build-up to the war in Iraq. Here, surely, were facts - or, indeed, a glaring absence of facts - that required piecing together. Here, surely, it was clear that political debate was operating on a curiously surreal level. We were being asked to attack a country on the basis that the weapons we knew (but couldn't prove) it had would definitely be used against us, especially if we attacked it. This Alice Through the Looking Glass logic has continued after the invasion. Now, it seems, it was necessary to have invaded Iraq to rid the world of the terrorist cells who have flooded into the country since it was invaded. The terrorist attacks in London and mainland Europe since are, officially, unconnected with the invasion of a country that was invaded because it had links with terrorist attacks in mainland Europe.

My favourite quotation from the eminently quotable George Bush is a remark he made last year about the constant attacks on US troops in Iraq: "The insurgents are being defeated; that's why they're continuing to fight." It's a stunning reversal of all logic. Measuring success in terms of how far you are from success. An even stranger utterance came from Tony Blair at Labour's 2004 Conference when he defended his actions by saying: "Judgments aren't the same as facts. Instinct is not science. I only know what I believe."

I only know what I believe. I find that one of the most chilling statements uttered by a seemingly rational politician. Apart from the fact that it overturns about 16 centuries of western philosophy and questions the entire principle of scientific inquiry, it's also, surely, how the Taliban get through their day.

Of course, I'm being selective in the way I have treated this logic. I have written my sentences with a deliberate aim of getting a laugh. I have treated it comically. But what else can I do? That's what I do. It was up to others to provide a more sober analysis. Except I just didn't see that happening. The media didn't stop to analyse the facts. Didn't comb Bush and Blair's speeches at the time to point out deficiencies in logic. And instead it was left for some of them to apologise much later for having trusted the PM too much, for having assumed that what he told the Commons about WMD was true. It's a shameful failure. The media didn't work. And it left a gap.

That's why I find myself stepping into that gap. Not just me, but many other humorists, satirists, comics, artists, people who make a virtue of the fact they distort logic for comic effect, but who still feel compelled to analyse that logic because no one else will. Everyone has analysed the result of the Hutton inquiry. But no one has analysed all the evidence given during it. Because the result, not the evidence, was deemed to have been the story.

But how can we expect the media to want to do anything more when the political debate they are meant to be reporting has become restricted to the point of non-existence? When politicians themselves want to debate image, postpone policy to the last moment, defer content until style has been sorted and sold, then there's a decreasing pool of ideas and arguments to analyse.

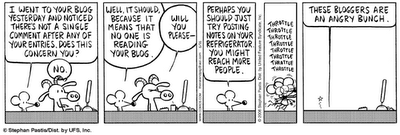

What amazes me is how much this has accelerated in the past five years or so; how much it seems to have gone past a tipping point where there's no longer anything factual left to talk about. Cameron sets up a webcam and a blog not because he has something new to say, but because he has a new medium in which to say something.

There is an emptiness in public argument waiting to be filled. That's where my lot come in again. If politicians fail to supply politics with content, is it any wonder people turn to other, more entertaining sources?

Given there is no absolute meaning, no hard, unquestionable kernel of truth at the centre of what we see, how can we take anything seriously ever again? Of course, we do, though, by turning to those who do offer narratives, even if they are fictional ones. Because they are better than no narrative at all. That's why I think comedy, and indeed any act of imagination, matters - and matters fundamentally. But this is not the sort of thing it should have been left to a comedian to say.

· This is an edited extract from the Tate Britain Lecture given by Armando Iannucci last night.